Reflection 21: 300 Rise of an Empire

Reaction Paper:

Movie Flick: 300 – The Rise of an Empire

Queen Gorgo: The Oracle’s words stand as a warning. A prophecy. Sparta will fall. All of Greece will fall. And Persian fire will reduce Athens to cinder. For Athens is a pile of stone and wood and cloth and dust. And, as dust, will vanish into the wind. Only the Athenians themselves exist, and the fate of the world hangs on their every syllable. Only the Athenians exist and only stout wooden ships can save them. Wooden ships, and a tidal wave of heroes’ blood.

- Can you please discuss the philosophies and religions of the Roman Empire?

Themistocles: My brothers. Steady your heart. Look deep into your souls. For your mettle is to be tested this day. If in the heat of battle you need a reason to fight on, you need only to look at the man who fights at your side. This is the why of battle. This is the brotherhood of men in arms. An unbreakable bond made stronger by the crucible of combat. You will never be closer than with those who you shed your blood with. For there is no nobler cause than to fight for those who will lay down their life for you. So you fight strong today. You fight for your brothers. Fight for your families. Most of all you fight for Greece.

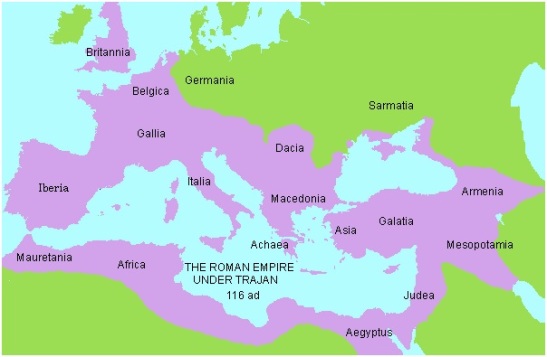

Rome was founded c. 500 bc. By 200 bc, it ruled most Italy, and in 150 bc, it conquered Carthage, the greatest power of the western Mediterranean at the time. By 150 bc, only three cities had over 100,000 people: Antioch, Alexandria, and Rome. By 44 bc, Rome would rule them all.

When Julius Caeser was assassinated in 44 bc (pretty much as Shakespeare described it!), that ended the vigorous Roman Republic. His adopted heir, calling himself Augustus Caesar, became first emperor. The Roman Empire would reach its greatest extent in 116 ad under the Emperor Trajan.

As you can imagine, the best minds of Rome were absorbed into politics, war, and economics. Few had the luxury of abstract philosophizing. Besides which, the Greeks had done that already, and look how far it got them: Quite a number of Greek philosophers wound up as Roman slaves, tutoring the youth of Roman aristocracy!

In this atmosphere, we find a powerful renewed interest, among the rich and poor alike, in religion. The old religion of Rome was given lip service, to be sure. But most saw the gods as little more than stories to scare naughty children (except when the adults themselves got frightened!). They were looking for comfort in uncertain times, and they found philosophy too dry. Many different cults — of the Great Mother, of Dionysus, of Isis from Egypt, Mithra from Persia, Baal from Syria, Yahweh from Palestine — became popular. Eventually, the Judaic sect we now call Christianity would prevail.

Why talk about religions and religious philosophies in a book on the history of psychology? There are actually a number of reasons. First, religion, philosophy, science, and psychology all come from the same human roots: We have a strong desire, even need, to understand the nature of the universe, our place in that universe, and the meaning of our lives. Religion included answers to these issues that have been psychologically satisfying as well as socially and politically powerful. Philosophy began separating from religion in the Greek and Roman times, and yet the great majority of people stuck with religion for their answers. In the renaissance and enlightenment, science began to separate from both religion and philosophy, and still the great majority remained loyal to religious dogma. And throughout much of history, religions have often taken a strongly anti-philosophical and anti-scientific position. Psychology inherits some of these issues, even into the modern era. It is valuable to any student of the history of philosophy, science, and psychology to understand the roots of religious belief and the power of those beliefs.

Neo-Platonism

Roman Philosophy was rarely more than a pale reflection of the Greek, with occasional flares of literary brilliance, but with few innovative ideas. On the one hand, there was the continuation of a sensible, if somewhat plodding, stoic philosophy, bolstered to some extent by the tendency to eclecticism (e.g. Cicero). On the other hand, there was the growing movement towards a somewhat mystical philosophy, an outgrowth of Stoicism usually referred to as Neo-Platonism. It’s best known proponent was Plotinus.

Plotinus (204-269) was born in Lycopolis in Egypt. He studied with Ammonius Saccus, a philosopher and dock worker and teacher of the church father Origen, in Alexandria. Plotinus left for Rome in 244, where he would teach until his death. He would have considerable influence on the Emperor Julian “the Apostate,” who tried unsuccessfully to return the Roman Empire to a philosophical version of Paganism, against the tide of Christianity.

On a military campaign to Persia, he encountered a variety of Persian and Indian ideas that he blended with Plato’s philosophy:

God is the supreme being, the absolute unity, and is indescribable. Any words (even the ones I just used) imply some limitation. God is best referred to as “the One,” eternal and infinite. Creation, Plotinus believed, is a continuous outflow from the One, with each “spasm” of creation a little less perfect than the one before.

The first outflow is called Nous (Divine Intelligence or Divine Mind, also referred to as Logos), and is second only to the One — it contemplates the One, but is itself no longer unitary. It is Nous that contains the Forms or Ideas that the earlier Greeks talked about. Then comes Psyche (the World Soul), projected from Nous into time. This Psyche is fragmented into all the individual souls of the universe. Finally, from Psyche emanates the world of space, matter, and the senses.

Spirituality involves moving from the senses to contemplation of one’s own soul, the World Soul, and Divine Intelligence — an upward flow towards the One. Ultimately, we require direct ecstatic communion with the One to be liberated. This made neo-Platonism quite compatable with the Christianity of ascetic monks and the church fathers, and with all the forms of mysticism that would flourish in the following 1800 years!

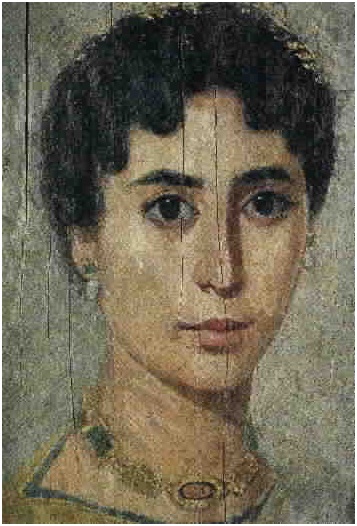

Another proponent of Neo-Platonism worth mentioning is Hypatia of Alexandria (370-415). A woman of great intellect, she became associated with an enemy of the Christian Bishop Cyril. He apparently ordered his monks to “take care” of her. They stripped her naked, dragged her from her home, beat her, cut her with tiles, and finally burned her battered body. The renaissance artist Raphael thought enough of her to include her in his masterpiece, The School of Athens.

Mithraism

One of the most popular religions of the Roman Empire, especially among Roman soldiers, was Mithraism. Its origins are Persian, and involves their ancient hierarchy of gods, as restructured byZarathustra (c. 628-c. 551 bc) in the holy books called the Avestas.

The universe was seen as involved in an eternal fight between light and darkness, personified by Ahura-Mazda (good) vs. Ahriman (evil). This idea probably influenced Jews while they were in Babylon, which is when they adopted HaShatan — Satan — as the evil one!

Within the Persian pantheon, Mithra was “the judger of souls” and “the protector,” and was considered the representative of Ahura-Mazda on earth.

Mithra, legend says, was incarnated into human form (as prophesized by Zarathustra) in 272 bc. He was born of a virgin, who was called the Mother of God. Mithra’s birthday was celebrated December 25 and he was called “the light of the world.” After teaching for 36 years, he ascended into heaven in 208 bc.

There were many similarities with Christianity: Mithraists believed in heaven and hell, judgement and resurrection. They had baptism and communion of bread and wine. They believed in service to God and others.

In the Roman Empire, Mithra became associated with the sun, and was referred to as the Sol Invictus, or unconquerable sun. The first day of the week — Sunday — was devoted to prayer to him. Mithraism became the official religion of Rome for some 300 years. The early Christian church later adopted Sunday as their holy day, and December 25 as the birthday of Jesus.

Mithra became the patron of soldiers. Soldiers in the Roman legions believed they should fight for the good, the light. They believed in self-discipline and chastity and brotherhood. Note that the custom of shaking hands comes from the Mithraic greeting of Roman soldiers.

It was operated like a secret society, with rites of passage in the form of physical challenges. Like in the gnostic sects (described below), there were seven grades, each protected by a planet.

Since Mithraism was restricted to men, the wives of the soldiers often belonged to clubs of Great Mother (Cybele) worshippers. One of the women’s rituals involved baptism in blood by having an animal- preferably a bull – slaughtered over the initiate in a pit below. This combined with the myth of Mithra killing the first living creature, a bull, and forming the world from the bull’s body, and was adopted by the Mithraists as well.

When Constantine converted to Christianity, he outlawed Mithraism. But a few Zoroastrians still exist today in India, and the Mithraic holidays were celebrated in Iran until the Ayatollah came into power. And, of course, Mithraism survives more subtly in various European — even Christian — traditions.

Christianity

Jesus was born, it is thought, about 6 bc. His name is Latinization of the Hebrew name Yeshua, which we know as Joshua. Legend has it that he was born in the small town of Bethlehem, to a virgin named Mary, the fiancée of a carpenter, Joseph. He grew up in Nazareth, part of a large Jewish family. He was apparently very intelligent and learned, for example, to read without formal education.

As a young man, he became very religious, and joined a group of ascetic Jews led by a charismatic leader named John the Baptist. When John was beheaded by local authorities for “rabble-rousing,” many began looking to Jesus for leadership.

He had 12 disciples from various towns and walks of life, and literally hundreds of other followers, men, women, and children. They wandered the area, in part to spread their beliefs, in part to stay ahead of unfriendly authorities.

At first, Jesus’s message was a serious, even fundamentalist, Judaism. He promoted such basic ethics as loving one’s neighbor and returning hatred with kindness. He particularly emphasized the difference between the formal religion of the priests and Jewish ruling class and the less precise, but more genuine, zeal of the simple people. Supporting the message was his apparent ability to heal the sick.

The Jews of his time felt oppressed by their Roman overlords, and many believed that their God would intervene on behalf of his people by sending a messiah — a charismatic leader who would drive out the Romans and establish a new Jewish state.

Many of Jesus’s followers, of course, believed that he was the messiah. At some point in his career, he began to believe this, too. Unfortunately, the Jewish authorities, answerable to the Romans, were concerned with his popularity, and had him arrested in Jerusalem.

He was condemned to death and crucified. His followers were clearly disappointed that the promised Jewish state was not delivered. But rumor of his coming back to life, and his appearance as a vision to several of his followers, reignited their faith. Many believed that he would return — soon! — to lead them.

As time went by, of course, it was clear that he wouldn’t be coming back in their lifetimes. The less messianic, more religious aspects of his teaching began to be emphasized, and his notion of the kingdom of God as within us, or at least as our heavenly reward, replaced the hoped-for Jewish state.

For better or worse, Judea was actually quite metropolitan — heavily “Hellenized” if not so “Romanized.” The same currents of thought in other parts of the empire where felt here as well. So the story of Jesus, as recorded in the gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke, began to be attached to ideas that were more properly neo-Platonist, gnostic, or even Mithraist!

The gospel of John, for example, is very different from the others, and refers to Jesus as the word, or Logos — a common Greek idea. Revelations, also attributed to John, but very different in style and content, has all the complex imagery of gnostic and Mithraist end-of-the-world stories, popular among the Jews at this time. It includes the idea of an eventual resurrection of the body — a concept that Jesus of the gospels did not promote, and which most Christians today do not believe in.

But it was Paul (c. 10 – c. 64 ad), a Romanized Jew, who would be most responsible for re-creating Jesus, whom he had never met, and never refers to by name. He is also responsible for divorcing this newly formed religion from its Jewish roots. It was Paul who introduced the idea that Jesus was the son of God and that only by faith in him could we hope to be “saved” from our inherent sinfulness.

For nearly a century, the early Christians were split into two hostile camps: One group followed Peter, one of Jesus’s original disciples. They were predominantly Jews and continued many Jewish traditions, as Jesus himself had done. The other group followed Paul, who was far more open to non-Jewish converts and waived much of Jewish law for those not born into it. The battle between these groups was, of course, won by Paul. Some critics suggest that Christianity ought to be called “Paulism!”

Both Peter and Paul were executed in Rome about 64 ad. Paul was beheaded. Peter was crucified upside-down (at his request, so as to avoid comparison with Jesus).

The Patrists, or church fathers, were the first Christian philosophers. In the eastern part of the empire, there was Origen of Alexandra (185-254); in the west, there was Tertullian of Carthage (165-220). Tertullian is best remembered for saying that he believed (in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ) precisely because it was absurd. Origen, on the other hand, had much more of the Greek in him, and pointed out that much of the Bible should be understood metaphorically, not literally. Keep in mind, though, that Origen cut off his own genitals because he took Matthew XIX, 12 literally!

The idea of the trinity, not found in the Bible itself, preoccupied the Patrists after Theophilius of Antioch introduced the concept in 180 ad. Tertullian felt that the trinity referred to God, his word (Logos), and his wisdom (Sophia). Origen was more precise, and said that it refers to the One (the father), intelligence (Logos, here meaning the son), and soul (Psyche, the holy spirit), following the Neo-Platonic scheme. Because the concept of the trinity is a difficult one, it was the root of many different interpretations which did not coincide with the official explanation. These alternative interpretations were labelled heresies, of course, and their authors excommunicated and books burned.

Origen also did not believe in hell: Like the Neo-Platonists, he thought that all souls will eventually return to the One. In fact, it is believed that Origen and the great neo-Platonist Plotinus had the same teacher — a dock worker/philosopher by the name of Ammonius Saccus.

The Patrists’ philosophies were for the most part the same: All truth comes from God, through the mystical experience they called grace (intuition, interior sense, light of faith). This clearly puts the church fathers in the same league as the neo-Platonists, and contrasts Christian philosophy with that of the ancient Greeks: To take truth on faith would be a very odd idea indeed to the likes of Socrates, Plato, Democritus, and Aristotle!

Christianity had certain strengths, with strong psychological (rather than philosophical) messages of protection, hope, and forgiveness. But its greatest strength was its egalitarianism: It was first and foremost a religion of the poor, and the empire had plenty of poor! Despite incredible persecution, it kept on growing.

Then, on the eve of battle on October 27, 312, a few miles north of Rome, Emperor Constantine had a vision of a flaming cross. He won the battle, adopted Christianity, and made it a legal religion with the Edict of Milan. In 391, all other religions were outlawed. But even then, Christianity still had competition.

Gnosticism

Gnosticism refers to a variety of religio-philosophical traditions going back to the times of the Egyptians and the Babylonians. All forms of Gnosticism involved the idea that the world is made up of matter and mind or spirit, with matter considered negative or even evil, and mind or spirit positive. Gnostics believe that we can progress towards an ultimate or pure form of spirit (God) by attaining secret knowledge — “the way” as announced by a savior sent by God.

The details of the various gnostic sects depended on the mythological metaphors used — Egyptian, Babylonian, Greek, Jewish, Christian… Gnosticism overall was heavily influenced by Persian religions (Zoroastrianism, Mithraism) and by Platonic philosophy.

There was a strong dependence on astrology (which they inherited from the Babylonians). Especially significant are the seven planets, which represent the seven spheres the soul must pass through to reach God. Magical incantations and formulas, often of Semitic origins, were also important.

When Christianity hit the stage, gnosticism adapted to it quickly, and began to promoted itself as a higher, truer form of Christianity. The theology looked like this:

At first, there was just God (a kind of absolute). Then there were emanations from God called his sons or aions. The youngest of these aions was Sophia, wisdom and the first female “son.” Sophia had a flaw, which was pride, which then infected the rest of the universe. We need to undo this flaw (original sin) but we cannot do it on our own. We need a savior aion, who could release Sophia from the bonds of error and restore her to her status as an emanation of God.

Worship among the gnostics included baptism, confirmation, and the eucharist. In fact, it is likely that several of the non-canonical gospels were written by Christian gnostics, and some say that John was a gnostic.

Gnosticism was strongly refuted by the early Christian Church in the 100’s and 200’s, as well as by the neo-Platonists, like Plotinus, who saw it as a corruption of Plato’s thought. In fact, of course, the reason for the animosity was more a matter of how similar gnosticism was to Christianity and neo-Platonism!

Manicheanism

Manicheanism was founded by Mani, born 215 ad in Persia. At 12, he was visited by an angel, who told him to be pure for 12 more years, at which time he would be rewarded by becoming a prophet. He would eventually consider himself the seal (i.e. the last) of the prophets, a title Mohammed would later claim for himself.

Forced to leave Persia, he wandered the east, preaching a gnostic version of Mithraism, with elements of Judaism, Christianity, and Buddhism. He considered himself an apostle of Jesus. When he returned to Persia, he was imprisoned and crucified.

In Manicheanism, Ormuzd (a corrupion of the name Ahura Mazda) is the good god, the god of light, creator of souls. There is also a god of evil and darkness — sometimes referred to as Jehovah! — who created the material world, even trapping Ormuzd’s souls in bodies. Another tradition has Ormuzd placing fragments of light — reason — in the evil one’s mannequins.

So there is light trapped inside of darkness! Mani believed that salvation comes through knowledge, self-denial, vegetarianism, fasting, and chastity. The elect are those who follow the rules most stringently. Their ultimate reward is a release of the light from its prison.

His followers were severely persecuted, by Persians and Romans alike. Still, the religion spread to Asia Minor, India, China, the Middle East, even Spain. It lasted in Europe until the 10th century ad and influenced later Christian heresies such as the Bogomils and the Cathars.

St. Augustine

St. Aurelius Augustine of Hippo (354-430) was a Manichean for 10 years before converted to Christianity in 386 ad. He would go on to become the best known Christian philosopher prior to the Middle ages.

He is best known to us for the first truly psychological, introspective account of his search for truth, in his Confessions. A hint of the intimate detail of his account can be gotten from one of his best known quotes: He prayed to God to “give me chastity and continence, but not yet!”

His philosophy is a loose adaptation of Plato to the requirements of Christianity. In order to reconcile the idea that God is good with the evil that obviously exists in the world, he turned to the concept of free will and our personal responsibility for sin. And he emphasized intentions over actions when it comes to assigning moral responsibility

There are, of course, problems with his arguments: If God is omniscient and omnipotent, he knows what we will do and in fact made us this way, so isn’t he still responsible for evil? Besides which, despite the admittedly great evil we human beings do to each other, aren’t there also natural disasters and diseases that could be considered evil, yet have nothing to do with our free will? These arguments would trouble philosophers even into the twentieth century. (See Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov for examples!)

Augustine became bishop of Hippo Regius (west of Carthage) in 395. He died in 430, during the seige of Hippo by the Vandals, a Germanic tribe that conquered North Africa (which was the “breadbasket” of Italy in those times!). You could say he lived through the fall of the Roman Empire.

The Fall of Rome

The Roman Empire was seriously declining. The economy began to stagnate. Too much money was being used to simply maintain the borders and unity of the empire. The cities began to deteriorate. City services declined, and hunger and disease severely hurt the poor. Many moved out to the country, where they found themselves working in the great latifundi — what we might call agribusinesses — as peasants and artisans. Free peasants turned over their ownership of land to these powerful landlords, in exchange for protection. In turn, these latifundi were ready-made mini-kingdoms for the barbarian chieftains who would be coming soon!

By the third century, the empire was being attacked from every direction. It was nobly defended by 33 legions (5000 men each). Internally, it was suffering from sheer size, and in 395, it officially split into two halves, the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire.

St. Aurelius Augustine of Hippo (354-430) was a Manichean for 10 years before converted to Christianity in 386 ad. He would go on to become the best known Christian philosopher prior to the Middle ages.

He is best known to us for the first truly psychological, introspective account of his search for truth, in his Confessions. A hint of the intimate detail of his account can be gotten from one of his best known quotes: He prayed to God to “give me chastity and continence, but not yet!”

His philosophy is a loose adaptation of Plato to the requirements of Christianity. In order to reconcile the idea that God is good with the evil that obviously exists in the world, he turned to the concept of free will and our personal responsibility for sin. And he emphasized intentions over actions when it comes to assigning moral responsibility

There are, of course, problems with his arguments: If God is omniscient and omnipotent, he knows what we will do and in fact made us this way, so isn’t he still responsible for evil? Besides which, despite the admittedly great evil we human beings do to each other, aren’t there also natural disasters and diseases that could be considered evil, yet have nothing to do with our free will? These arguments would trouble philosophers even into the twentieth century. (See Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov for examples!)

Augustine became bishop of Hippo Regius (west of Carthage) in 395. He died in 430, during the seige of Hippo by the Vandals, a Germanic tribe that conquered North Africa (which was the “breadbasket” of Italy in those times!). You could say he lived through the fall of the Roman Empire.

The Fall of Rome

The Roman Empire was seriously declining. The economy began to stagnate. Too much money was being used to simply maintain the borders and unity of the empire. The cities began to deteriorate. City services declined, and hunger and disease severely hurt the poor. Many moved out to the country, where they found themselves working in the great latifundi — what we might call agribusinesses — as peasants and artisans. Free peasants turned over their ownership of land to these powerful landlords, in exchange for protection. In turn, these latifundi were ready-made mini-kingdoms for the barbarian chieftains who would be coming soon!

By the third century, the empire was being attacked from every direction. It was nobly defended by 33 legions (5000 men each). Internally, it was suffering from sheer size, and in 395, it officially split into two halves, the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire.

In the 400s, the Huns entered Europe from the Russian steppes, and got as far as Chalons, near Paris. They spread terror everywhere they went. Their empire collapsed in 476, but not before they set dozens of German tribes in motion towards the Roman Empire.

The Romans fought some off, paid some off, and let some in to protect the borders. Most of the mighty legions were eventually composed of German soldiers! One rather large tribe, the Visigoths (western Goths), began to move towards Italy from their settlements in the Balkans. In 410, they destroyed Rome. The western half of the Roman Empire was for all intents and purposes dead and in the hands of the various invaders.

The Eastern Roman Empire was also in decline and was plagued by wars, external and internal. Emperor Justinian (527 – 565) tried but failed to reconquer Italy and sent the Eastern Empire into financial crisis. His efforts to discourage pagan philosophies and eliminate Christian heresies would eventually lead to much dissatisfaction with his rule. On the other hand, Justinian codified Roman law and adapted it to Christian theology, and he promoted great works such as the building of the Hagia Sophia, with its incredibly large dome and beautiful mosaics.

Barbarians at the gates were only part of the Empire’s problems, however. There was famine in the remnants of the Roman Empire on and off from 400 to 800. There was a plague in the 500’s. The Empire’s population dropped by 50%. The city of Rome’s population dropped 90%. By 700, only Constantinople– capital of the eastern Roman Empire — had more than 100,000 people.

In the late 600’s, Arabs conquered Egypt and Syria (up till then still a part of the Eastern Empire), and even attempted to take Constantinople itself. In the 700’s, Europe was attacked by Bulgars (a Mongol tribe), Khazars (a Turkish tribe which had adopted Judaism), Magyars (the Hungarians), and others. The Eastern Empire would see the Turks take Anatolia (appropriately renamed Turkey) in 1071, and finally take Constantinople in 1453.

In the meantime, western Europe was ruled by various size gangster-like hierarchies of illiterate warriors. The great mass of people were reduced to slave-like conditions, tilling the soil or in service jobs in the greatly reduced cities. We don’t call ‘em the dark ages for nothing!

But, when the sun sets on one civilization, it is usually rising somewhere else….

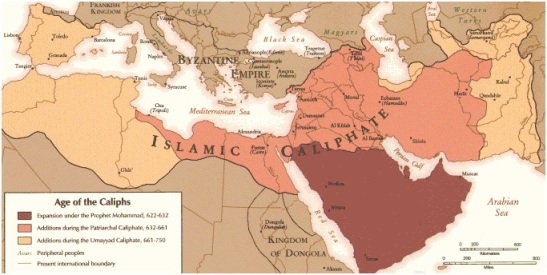

Islam

So, as the Roman Empire faded into the sunset, the opportunity for other civilizations to make a mark arose. I doubt that anyone at the time would have guessed that the major contender would come from the relatively desolate western coast of Arabia. Arabia could only marginally sustain its population agriculturally. But, positioned nicely between the wealthy empires to its north and the untapped resources of Africa to its south — and later the ocean roots to India and beyond — it managed to provide its people with the option of lucrative trade.

Mohammed was born 569 ad in Mecca, a merchant town near the Red Sea. His mother died when he was six, so he was raised, first by his grandfather, later by his uncle. He was probably illiterate, but that was the reality for most Arabs of the time.

At 26, he married a wealthy widow 14 years his senior, who would be his only wife until she died 26 years later. He would have ten more wives — but no living son. He and his first wife had a daughter, Fatima, who would become a significant character in Islamic history. She married Mohammed’s adopted son, Ali.

As he got older, he became increasingly religious, and sought to learn about Judaism and Christianity. He began to meditate alone in the desert and local caves.

In 610 ad, Mohammed fell asleep in a cave, when tradition has it that the angel Gabriel appeared to him and told him he would be the messenger of God (Allah*). He would have this experience repeatedly throughout the rest of his ife. Each time, the angel would provide him with a lesson (sura) which he was to commit to memory. These were eventually recorded, and after his death collected into the Islamic holy book, the Quran (or Koran).

He preached to the people of Mecca, but was met with considerable opposition from pagan leaders. When the threat of violence became clear, he left Mecca for the town of Medina, to which he had been invited, with some 200 of his followers. Here, he was much more successful, and eventually he took over secular authority of the the town.

Relations with the pagan families of Mecca continued to deteriorate, and relations with the Jews of Medina, at first promising, deteriorated as well. An alliance between the Meccan families and the Medina Jews fought Mohammed’s followers over the course of several years.

In 630, Mohammed took Mecca. Within two more years, all of Arabia was under his control, and Islam was a force to be reckoned with. Mohammed died June 7, 632.

Mohammed’s basic message was simple enough: We must accept Allah as the one and only God, and accept that Mohammed was his prophet. Say words to this effect three times, and you are a Moslem.

Islam means surrender, meaning that we are saved only by faith. Allah, being all-knowing, knows in advance who will and who will not be saved. This idea (which we will see again among the Protestants in Europe) tends to encourage bravery in battle, but it also tends to lead a culture into pessimistic acceptance of the status quo. But that would not happen to Islam for many hundreds of years!

The Quran says that some day (only Allah knows when), the dead will rise and be reunited with their souls. They will be judged. Some will be cast into one of the seven levels of hell. Some will be admitted into paradise — described in very physical, even hedonistic, terms. Much of this scenario came from the Jews, who in turn got it from the Persians.

Islam is very rule-oriented, blending the religious with the secular. Church and State are one. In the Quran, there are rules for marriage, commerce, politics, war, hygiene — very similar to the Jewish laws, which Mohammed imitated. Among those rules, Moslems are not to eat pork or dog meat and may not have sex during a woman’s period, just like the Jews. Mohammed added a rule against alcohol. The society Mohammed envisioned is approximated by such authoritarian states as Saudi Arabia and Iran today.

Marriage was encouraged, and celibacy considered sinful. Polygamy was permitted, within limits. Women, as in Judaism and Christianity, were clearly secondary to men, but were not to be considered property. They were equal to men in most legal and financial dealings, and divorce, while easy, was strongly discouraged. Likewise, although slavery was not condemned, many rules were designed to humanize the institution.

Mohammed and the Moslems were generally accepting of Jews and Christians (“people of the book”), but intolerant of pagans. War and capital punishment were clearly condoned and practiced by the prophet: “And one who attacks you, attack him in like manner” (ii, 194).

The Arabic culture and language, and the religion of Islam, soon would dominate much of the world, from Spain and Morocco to Egypt and Palestine to Persia and beyond. For a while, it would present a progressive, tolerant face, and Moslem philosophy would rival that of the ancient Greeks.

* Allah is the Arabic word meaning “the God.” It comes from the same root as the Hebrew Elohim, and ultimately comes from the Cananite word El, which referred to the father of all the gods.

2. Can you discuss the film historical facts and fictions?

Queen Gorgo: It begins as a whisper… a promise… the lightest of breezes dances above the death cries of 300 men. That breeze became a wind. A wind that my brothers have sacrificed. A wind of freedom… a wind of justice… a wind of vengeance.

The sequel to 300 lives up to its predecessor’s reputation, with more than enough blood, gore and sex to sooth the most fervent of fans. What set apart the first 300 movie was its manipulation of historical events to create a box office spectacle of the grandest kind. But the salient points of the last stand at Thermopylae were entirely accurate – Ephialtes may not have been a hunchback, but he sure as hell betrayed the Greeks, so much so that his name became a synonym for “nightmare”. Bearing that in mind, how does “Rise of an Empire” stack up to 300 when it comes to real history? Let’s take it step by step.

Characters

Themistocles

“Rise of an Empire’s” replacement for Leonidas is one of the mocked “boy-lover” Athenians, Themistocles.

In the movie: Themistocles led the Athenians into battle at Marathon ten years earlier, leading a surprise attack on the disembarking Persian forces of King Darius – Xerxes’ father. He even shoots the arrow that fells the king of Persia himself. Themistocles leads the charge to unite Greece in order to face the Persian threat. At the Battle of Salamis he smashes the Persian fleet and slays Artemesia, the enemy commander.

In truth: Themistocles was one of the subordinate generals leading the Athenian army at Marathon. He was by no means its leader. That title went to Miltiades, a dethroned tyrant whom the Athenians entrusted to defeat the Persians. Themistocles played no part in killing Darius – because neither Darius nor his son Xerxes were anywhere near Marathon at the time. The Greek cities were too small a prize at the time for the king himself to deal with. Defeat at Marathon, of course, changed that.

Themistocles was no doubt instrumental in forming the league of Greek city-states that went to battle at Salamis. He also was the founder of the Athenian navy, securing the construction of hundreds of ships in a remarkably short span of time. He led the fleet brilliantly into battle at Salamis and elsewhere during the Persian Wars. However, once again, he did not kill Artemesia as “Rise of an Empire” tells us. Sadly, the brave cavalry charge over and under the roiling waters of Salamis is not so much a fiction as it is a wet dream.

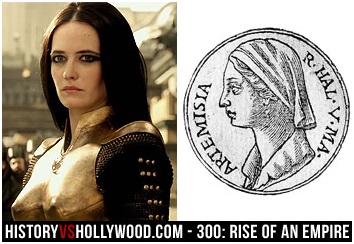

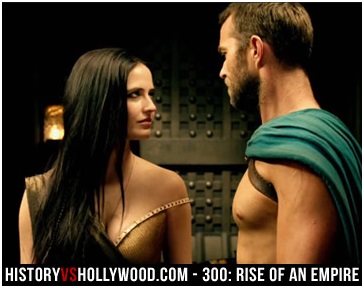

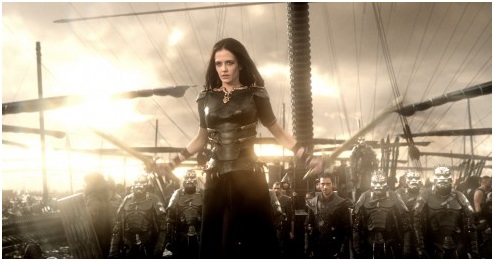

Artemesia

Eva Green plays the most Persian of femme fatales, a bloodthirsty, slave-driving, double-bladed, vengeful, curse of a woman.

In the movie: Artemesia cultivates a hatred of the Greeks after her family is slaughtered by hoplites and she is whored by them until well into her teens. She develops her skills at the Persian court after one of Darius’ emissaries saves her. Soon she becomes Darius and Xerxes’ most trusted commander.

She leads the fleet in the Greek campaign. Defying Xerxes’ orders to be cautious, she takes the fleet into Salamis, nearly smashes Themistocles’ fleet (after trying to sleep with him, of course), and then watches the Persian navy meet its doom at the hands of Sparta and the resurgent Greeks coming to the rescue. She dies with a blade thrust through her stomach by, guess who? Themistocles.

In truth: Little is known about her, but Artemesia was most definitely not a captured slave who worked her way up the ladder after getting a lucky break. In fact, she was a queen.

The Persians had not much of a navy of their own, so they drew upon the fleets of all the subordinate kings of their empire. Artemesia was but one of them, albeit the only female. Far from commanding the entire fleet, though, Artemesia brought perhaps as little as five ships to join the Persian armada – according to Herodotus. She didn’t die at Salamis – a battle she told Xerxes they shouldn’t fight, not the other way around. Artemesia is said to have survived by smashing through one of the Persians’ own ships – though, apparently, nobody told Xerxes. He gave her a full set of Greek armour as reward for her cowardice.

The Battle

In the movie: Sparta’s queen refuses to send its fleet to join the united navy. Themistocles’ inadequate navy therefore bravely confronts the Persians day after day while Leonidas holds out at Thermopylae. They are facing a force of thousands of ships, against which their own fleet pales in comparison. The armada is manned by “farmers” and “tradesmen” untested in war. Against the odds, the ships hold out against Artemesia’s wrath until, finally, she undoes the Greeks with burning tar, causing them to flee with a bare handful of boats left.

At Salamis, Themistocles rouses the Greek navy to make their own last stand, with a battleplan you know is just made for the big screen – send all the ships screaming towards the center of the line, where Artemesia can be killed, thus throwing the Persians into disarray. As the tiny Greek force looks to be on the verge of annihilation, surrounded and being cut down by Persians on all sides, salvation arrives in the form of Sparta’s ships and those of other Greek allies. The reinforcements take the Persians in both flanks and the day is won.

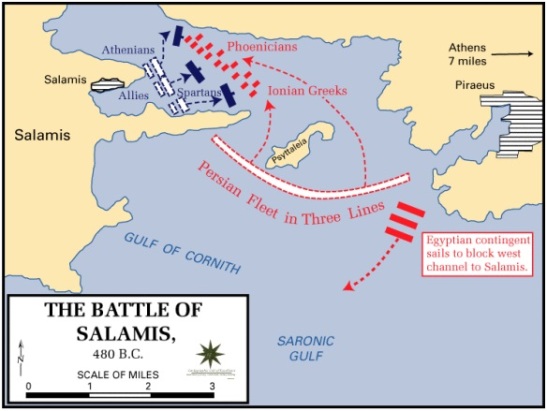

In truth: Salamis truly was a momentous victory. It forced Xerxes to flee back to Asia and played a huge apart in the eventual defeat of the Persians. However, “Rise of an Empire” makes almost no attempt to maintain the historicity of the battle. Nothing, I repeat, nothing happened the way it did in this admittedly fantastic movie.

Less of a headlong charge and more of an ingenious trap – detracting not at all from Themistocles’ brilliance.

To understand the significance of Salamis, we must understand how the Persians came to Greece. As seen on screen, they crossed an enormous ‘pontoon bridge’ over the Hellespont, the strait that divides Europe from Asia. Such a bridge is built by tying hundreds of boats to the shore on either side and laying planks atop them. Even a layman can see that this is a rather fragile means of transport.

Xerxes needed a massive fleet to ensure the Greeks could not attack this bridge and cut him off from his empire in Asia. Such an event would be a catastrophe. The Persian army would be stranded and civil war might ensue back home.

Did the Spartans hold back their fleet from the resistance? Most certainly not. Spartan ships were present throughout the campaign. Together, the Greeks fought Xerxes’ navy to a standstill at Artemisium while the Battle of Thermopylae raged on land. However, when Leonidas fell their strategy was ruined, and Themistocles withdrew his fleet to the bay at Salamis. He did not withdraw, as the movie tells us, after his ships were burnt and battered beyond recognition by the Persian fleet. As a matter of fact, the battles at Artemisium were inconclusive and the Persians had no clear advantage. Themistocles pulled back his navy because the allied strategy depended on defense both at Artemisium and the Hot Gates.

With the Spartan rear guard gone, his position was compromised, and Salamis was to be the new base of operations. The odds were stacked against the Greeks, but not as heavily as one might think. The Persians, after losing a third of their fleet to storms and another 200 ships at Artemisium, now only outnumbered the Greeks by 100 ships – not the advantage of thousands described in “Rise of an Empire.”

As mentioned, Artemesia did not hastily rush the Persian ships into battle against Xerxes’ wishes – firstly, she didn’t command much more than her own squadron in the armada; secondly, she told Xerxes that seeking battle was a bad idea. But the God-King insisted, and so it began. Not how it played on screen, though. Not at all.

Themistocles sent a hoax defector to tell Xerxes that the Greek coalition was falling apart. Sheltered in the straits of Salamis lay the Greek armada. All Xerxes needed do to win, he said, was to enter the protected waters and wait to attack the fleeing ships. This played to Xerxes ego, and he authorised such a plan.

It was a trap, of course. The next day, the Persian fleet entered headlong into the strait’s eastern end, while a small contingent went round to block the western entrance. However, the Greeks were fully prepared – the Persians found no ships rushing to surrender or escape as they’d expected, and now a true battle was on hand.

In the exceptionally narrow straits, the Persian fleet’s numbers counted for nothing. Their boats congested the channel and could not manoeuvre, while the Greeks rammed and cut them to pieces from all sides. Artemesia escaped, but the Persian fleet was vanquished while Xerxes watched (tearfully, one presumes) from his throne on the shore.

So, there was no “boo-hoo!” moment when the Greek ships suddenly appeared on the horizon to save their comrades. All of Greece’s ships were already at Salamis, waiting for the Persians to waltz into their lair. A massive victory – but a far different one than told in the theatre. Yet the writers did indeed put an approximation of the true Salamis into their movie – you would recognise the similarities to the scene early on when the Persian boats chase their enemies into the fog, suddenly finding themselves trapped in a narrow channel and attacked on all sides. The movie scene, while clearly inspired by history, is set at the wrong time, taking place before the retreat to Salamis had occurred.

Epilogue

“Rise of an Empire” shows Xerxes turning away in disgust from the spectacle before him. Such a moment is easily imagined, for we know what happened next. Xerxes fled from his army, the massive force of a hundred nations he had brought into Europe. The king rode back into Asia and away from the disaster that was quickly coming down upon his host.

On closer inspection, this seems strange. On land, Xerxes had not yet been defeated. The losses at Thermopylae were, in the grand scheme of things, irrelevant, and the loss of his ships did not impair his army – now in occupation of most of the Greek mainland. However, as stated earlier, it was not outright defeat he feared as much as he seemed to fear not being able to escape from such a defeat. Leonidas had disabused him of the notion that his army was invincible. Now, the Greek fleet could easily destroy the bridge at the Hellespont. Xerxes could not allow himself to be stranded in Europe, far from the center of his empire, where machinations and rebellious strands could cause his realm to slip from his hands too quickly. So he fled, and, sure enough, the following year, his great army was also destroyed by the Greeks – at Plataea, led by the Spartans, just as the original 300 stated.

Why, though, is this movie titled “Rise of an Empire”? Which empire is it talking about? The Persian Empire? No. The Athenian Empire. What the movie doesn’t tell you is what came after Salamis and Plataea. The Spartans, having saved Greece, went back home. Athens, however, seized the moment, attempting to gain control over a myriad of Persian territories far from the city, while dominating its neighbours nearer to home. The Persian Wars would drag out for half a century, and gave Athens dominion over almost the entire Aegean coast and more. Athens grew fabulously rich, and the world’s first democracy became the Western world’s first true empire – irony at its best.

Athen’s empire in 431BC. History is nothing but ironic – half a century after salvaging their democracy from being swallowed into the Persian Empire, the Athenians had an empire of their own, built by subjugating dozens of Greek cities. For most of the 5th century BC, Athens and her wooden ships would completely dominate the Aegean.

3. Why would you say the film doesn’t know its Artemisia from it’s elbow?

Queen Gorgo: No terms were reached. Xerxes’ messenger was… Well, he was rude and he lacked respect. He didn’t understand the same threats made in Thebes and Athens would not work here. This is the birthplace of the world’s greatest warriors. Men whose king would stand and fight and die for any one of them. Xerxes’ messenger… did not understand this is no typical Greek city-state. This is Sparta.

Themistocles: It was clear to the messenger there’d be no Spartan submission?

Queen Gorgo: It was clear.

300: Rise of an Empire (2014)

Director: Noam Murro

Entertainment grade: D–

History grade: Fail

The battle of Salamis in 480BC was the major turning point in the Greco-Persian wars.

Themes

The first few minutes of 300: Rise of an Empire set out its wares: there’s beheading, jiggling breasts, rape, a world view derived from Fox News (Darius the Great of Persia invaded Greece, we learn, because he was “annoyed by Greek freedom”), macho military anachronism (Greek hero Themistocles is skilled in something called “Athenian shock combat”), blood and mud both spurting around in 3D on the screen like thick black slime, waxed chests, teeny tiny leather man-panties, a portentous voiceover and racism. If you love all that stuff, saddle up your battle rhino: the wilful massacre of ancient Mediterranean history that was300 is back.

People

At the battle of Marathon in 490BC, Themistocles (Sullivan Stapleton) hacks his way through a beachful of Persians. He spies Darius the Great watching the battle from a ship, and shoots him with an arrow. “Themistocles knew in his heart he had made a mistake,” intones the voiceover. You bet he did. The real Darius wasn’t at the Battle of Marathon, and Themistocles didn’t kill him. The Achaemenid King of Kings lived for another four years and died naturally following an illness. But no, the film isn’t owning up to having blooped: it is suggesting that by killing Darius, Themistocles has opened the way for Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro) to take over. You know, the massive gilded embodiment of orientalism from last time round.

Military

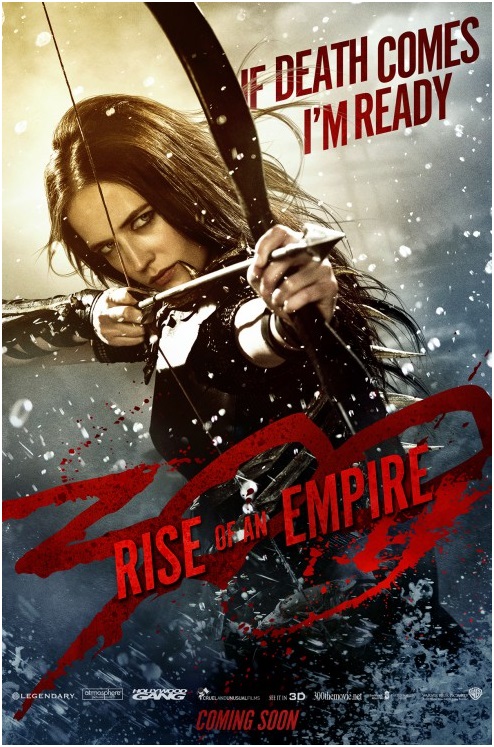

Cut to the Achaemenid empire, and to a palace which is probably supposed to be Persepolis, but looks more like the headquarters of the Tyrell Corporation in Blade Runner. Darius is dying so slowly from his arrow wound that he has managed to travel 4,000 kilometres with it still sticking out of his chest. Xerxes is distraught; so is Artemisia (Eva Green), the Achaemenids’ most ruthless military commander and most total babe. In real life, Artemisia was queen of Halicarnassus. She was indeed a famous and heroic fighter, prompted to join the campaign, according to Greek historian Herodotus, “by the formidably masculine cast of her bravery”. She was not what 300: Rise of an Empire turns her into: a peasant girl brutalised by years of rape (this film misses no opportunity to show or imply rape) who has malevolently blossomed into Bondage Nymphomaniac Revenge Barbie.

Slavery

Most of the film is taken up with sea-battles, especially the battle of Salamis. These battles are – it must be said – spectacularly staged. Historians may be irritated to see ships rowed by galley slaves, a legend popularised by the book and movie Ben-Hur but rarely seen in the classical world. Rowing was a skilled profession and therefore not considered suitable for slaves. Aristotle states specifically in his Politics that the fact ordinary citizens rowed the ships at Salamis strengthened Athenian democracy.

War

Themistocles and Artemisia indulge in a brief, ahistorical bout of hate sex, which fails to avert the war but does mean viewers get to see more breasts. The film is vaguely right in showing the Greeks drawing the much larger Persian fleet into the narrow Straits of Salamis, so as to negate the advantage of their greater numbers. Historian and translator of Herodotus’s Histories Tom Holland, whose own book Persian Fire is a gripping account of the Greco-Persian wars, admired the first 300 film for its authentically Spartan perspective. Yet this one, he has said, “is to the Herodotean narrative of the Persian Wars rather what Hogwarts is to the average British school”, adding: “In one way, the battle of Salamis is very true to the Herodotean narrative: it’s almost impossible to work out what’s going on.” Distractingly, almost every scene has been overlaid by VFX of sparks, cinders and bits of dust floating around in the air, so that the whole affair begins to resemble a gay neoconservative snowglobe.

Sea-battle sequences in 300: Rise of an Empire are spectacularly staged.

Analogies

The Persians unleash a huge metal bomb-ship that chugs out pitch and a detachment of frogmen suicide bombers. Are there huge metal bomb-ships and suicide bombers in Herodotus? No. But without them you may not have realised just how racist and silly this film is prepared to be. Meanwhile, the Spartans turn up at the last minute to save the day (they didn’t) led by Queen Gorgo (they weren’t) with hundreds of ships (they had 16). Themistocles slays Artemisia with heavy-handed symbolism by thrusting his great big sword lustily into her tummy. The real Artemisia escaped at the Battle of Salamis, provoking Xerxes to declare: “My men have become women, and my women men.” She was trusted by Xerxes as an adviser after the battle, and was charged with the care of some of his bastard children. Her ultimate fate is not known. Themistocles’s is, though this film doesn’t mention it: he joined the Persians.

Verdict

Please don’t make a third film.

4. Can you discuss how this film portrayed history vs. Hollywood?

Artemisia: It’s a curious thing for a simple ship guard… to not lower his eyes when questioned by me. That could’ve been just a lack of discipline.

[Grabs His Hands]

Artemisia: But a man’s hands do not lie. They can reveal every imperfection and flaw in his character. You see, your hands are not rough enough to work the rigging of this ship. I know every single man beneath my lash. Can you explain to me how I don’t know you?

Scyllias: Forgive me, Commander. Let me introduce myself.

[He bows, Unsheathes a Knife and Kills Two Soldiers]

Reel Face:

Sullivan Stapleton

Born: June 14, 1977

Birthplace:

Melbourne, Australia

Real Face:

Themistocles

Born: c. 524 BC

Birthplace: Athens, Greece

Death: 459 BC, Magnesia on the Maeander (likely of natural causes)

Reel Face:

Eva Green

Born: July 5, 1980

Birthplace:

Paris, France

Real Face:

Artemisia I of Caria

Born: 5th Century BC

Birthplace:Halicarnassus, Caria, Persia

Death: 5th Century BC

Reel Face:

Rodrigo Santoro

Born: August 22, 1975

Birthplace:

Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Real Face:

Xerxes

Born: 519 BC

Birthplace: Persia

Death: 465 BC, Persepolis, Persia(assassination by stabbing, likely by his political advisor Artabanus)

Reel Face:

Lena Headey

Born: October 3, 1973

Birthplace:

Hamilton, Bermuda

Real Face:

Queen Gorgo

Born: c. 513 BC

Birthplace: Sparta, Greece

Though not Gorgo, this unidentified Spartan artifact from that period reflects how she would have presented herself.

Reel Face:

Immortals (300: Rise of an Empire Movie)

The Persian Imperial soldiers in the movie, inspired by Frank Miller’s graphic novel ‘300’ and

his follow-up ‘Xerxes.’

Real Face

Immortals (Persian History)

The Immortals were an Imperial Guard division that protected the Persian rulers during the time of the Greco-Persian Wars.

- I made some research about Artemisia and I found out that she was very different from the movie. She was a very brave woman commander, but she was in love with Xerxes, so it’s a complete different story. And I kind of got inspired more by Cleopatra, or Lady Macbeth, you know, kind of bloodthirsty characters…-Eva Green (comInterview, 2014)

Questioning the Story:

Did Artemisia really have a hunger for warfare?

Yes. Herodotus, also known as the “Father of History,” makes numerous references to Artemisia as he recounts the events of the Greco-Persian war. He describes her as a ruler who did not lead passively, and instead, actively engaged herself in both adventure and warfare. “…her brave spirit and manly daring sent her forth to the war, when no need required her to adventure. Her name, as I said, was Artemisia…” –The Histories

Was Artemisia really known for her cunning tactics and intelligence in combat?

Yes. In exploring the 300: Rise of an Empire true story, we came upon the works of Polyaenus, the 2nd century Macedonian writer. He describes an example of the real Artemisia’s intelligence in combat. He tells of how she would carry two flags on board her ship, one a Persian flag and the other the flag of her enemy, Greece. Artemisia would fly the Greek flag as she approached an unsuspecting Greek warship. Once she was upon her enemy, she would then unleash the full force of her Carian fleet.

Similar to Artemisia (Eva Green) in the 300: Rise of an Empire movie, the real Artemisia, Queen of Caria, was a cunning conqueror with a penchant for warfare.

In another example described by Polyaenus, Artemisia prepared a great festival to be held approximately a kilometer away from the ancient city of Latmus, which she planned to conquer. The festival drew the attention of the nearby city, and both civilians and soldiers left the city to see what the fuss was all about. After the city emptied itself, Artemisia launched a full-scale invasion, conquering Latmus with little resistance.

Were the Greeks really angered that a woman had taken up arms against them?

Yes. According to Herodotus, the united Greeks even offered a reward of 10,000 drachmas for Artemisia’s capture.

What do the events in 300: Rise of an Empire have to do with the events in the original movie 300?

300: Rise of an Empire is a prequel, a side-sequel, and a sequel to the original film, 300 (2007), with the events in the follow-up taking place before, during, and after the events in the original. The first battle that takes place in the 300: Rise of an Empiremovie is the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. This happens ten years prior to the events in 2007’s300 movie. Athens victory over Persia at Marathon, Greece sets the stage for the motivations behind Xerxes’s transformation into the movie’s fictional God King.

The second battle that occurs in 300: Rise of an Empire, the Battle of Artemisium (a 480 BC naval engagement), took place concurrently with the Battle of Thermopylae that unfolds in the original movie, 300. It was Themistocles who proposed that the Greeks attempt to stop the Persian advance by confronting them on land at the narrow strait at Thermopylae. Leonidas and the 300 Spartans undertook the task, which is chronicled in the movie 300, with the Spartans eventually being overtaken by the Persian forces. At the same time, the Greek navy attempted to block the Persians on the water in the Straits of Artemisium. However, they were forced to retreat after the defeat at Thermopylae.

Persian king Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro), with ax in hand, sits atop his horse as he looks over his fallen enemy, the Spartan king Leonidas (Gerard Butler). From 300: Rise of an Empire.

The third battle in Rise of an Empire, the Battle of Salamis, occurs after the Persians have advanced and burned Athens to the ground. Like in the movie, Themistocles had learned from the mistakes he made in the Battle of Artemisium, realizing that Greece likely did not stand a chance when confronting the larger Persian navy in the open water. He figured out that if the Greeks were to win, they would need to engage in close combat with the Persians in straits that were more narrow, such as those at Salamis. There, the large Persian warships could be outmaneuvered by the smaller Greek ships.

Had the Athenian general Themistocles been born into poverty?

Yes. According to historians Herodotus and Plutarch, the brave Athenian general Themistocles was not born into wealth. His father, Neocles, was an ambiguous Athenian citizen of modest means. It is believed that his mother was an immigrant. Other children kept Themistocles at a distance. It didn’t bother him much, because as other children were off playing together, Themistocles was studying and sharpening his skills. As described by Plutarch, his teachers would say to him, “You, my boy, will be nothing insignificant, but great one way or another, either for good or for evil.”

In researching the 300: Rise of an Empire true story, we learned that Themistocles less than modest upbringing benefited him in the newly democratic government of Athens. He campaigned in the streets and could relate to the common and underprivileged in a way that no one had before, always taking time to remember voters’ names. He was elected to the highest government office in Athens, Archon Eponymous, by the time he was thirty.

Was Themistocles really responsible for Greece’s strong navy?

Yes. Themistocles always believed in building up the Athenian navy. He knew that the Persians could only sustain a land invasion if their navy was able to support it from the coastal waters. However, most Athenians, including the Athenian generals, did not agree with Themistocles. They did not believe that a Persian invasion was imminent, and they thought that the Athenian army was strong enough to make up for any shortcomings with regard to the navy.

To get his wish for a stronger navy, Themistocles used his political position to lie and mislead the Athenians into believing that the rival nearby island of Aegina posed a threat to merchant ships. Accepting his argument, the Athenians decided to invest in the navy, leaving Athens with the most dominant naval force in all of Greece. Therefore, it can be argued that Greek civilization was saved by a lie.

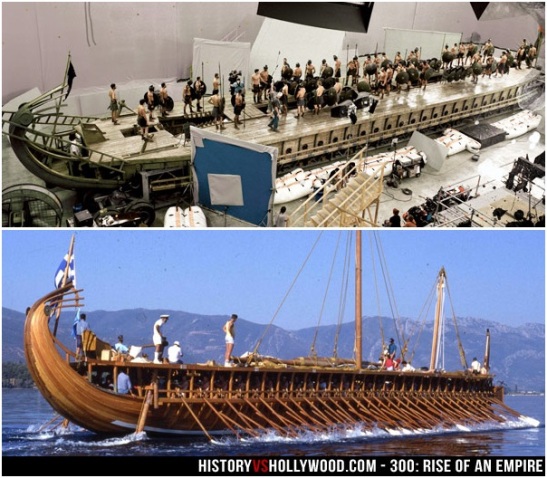

Top: Actors stand on the deck of an Athenian trireme (ancient vessel) constructed on a sound stage for the movie. Bottom: A seaworthy reconstruction of a trireme, the Olympias, was launched in 1987.

Did Themistocles really kill Xerxes’s father, King Darius?

No. The true story behind 300: Rise of an Empire reveals that Themistocles did not kill Xerxes’s father, King Darius I of Persia (Darius the Great), with an arrow at the Battle of Marathon. King Darius died approximately four years later in 486 BC of failing health. It was then that Xerxes, the eldest son of Darius and Atossa, became King, ruling as Xerxes I.

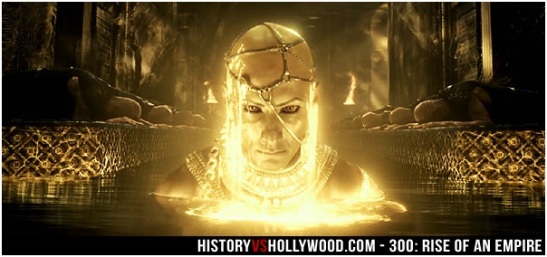

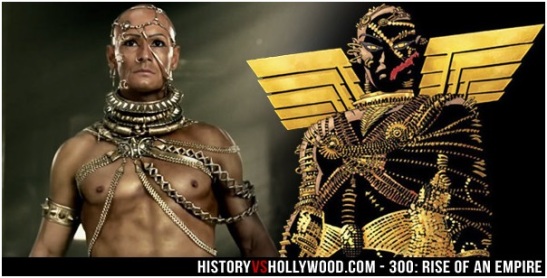

Did Xerxes really transform into a God King?

No. As you probably guessed, the real Xerxes did not transform into a supernatural God King like in the movie (pictured below). In fact, Xerxes’s motivation for his transformation did not even exist in real life, since Themistocles did not kill Xerxes’s father at the Battle of Marathon. This highly fictionalized version of Xerxes comes from the mind of Frank Miller, the creator of the 300 graphic novel and the still unpublished Xerxes comic series.

Persian king Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro) transforms into the fictional God King in 300: Rise of an Empire.

Was Artemisia’s family murdered by Greek hoplites, after which she was taken as a slave?

No. In the 300: Rise of an Empire movie, a young Artemisia (Caitlin Carmichael) watches as her family is murdered by a squad of Greek hoplites. She then spends several years being held as a sex slave in the bowels of a Greek slave ship. She is left to die in the street and is helped by a Persian warrior. She soon finds herself training with the finest warriors in the Persian Empire, hoping to one day exact revenge on Greece. This backstory for Artemisia was invented by Frank Miller and the filmmakers to explain the motivations behind Artemisia’s ruthless thirst for vengeance in the film.

Did Artemisia have a husband?

Yes. Queen Artemisia of Caria, portrayed by Eva Green in the movie, became queen when she was wed to the King of Caria. Ancient Greek historian Herodotus never mentions the king by name in his writings titled The Histories. Little is known about Artemisia’s husband except that he died when their son was still a boy. Following his death, Artemisia became the ruler of the affluent kingdom of Caria.

Left: Artemisia (Eva Green) clad in armor in 300: Rise of an Empire. Right: A 16th century coin-like portrait of Artemisia from Guillaume Rouillé’s book Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum.

Did Artemisia have any children?

Yes. Artemisia I of Caria had a son named Pisindelis (not shown in the movie), who was still a boy when his father died and his mother took over as ruler.

Was Artemisia the only female commander in the Greco-Persian wars?

Yes. According to the writings of Herodotus, Artemisia I of Caria was the only female commander in the Greco-Persian wars. Like in the movie, she was an ally of Xerxes and served as a commander in the Persian navy.

Did the Greek city-states really band together against the invading Persian Army?

Yes. In the 300: Rise of an Empire movie, we see Queen Gorgo of Sparta (Lena Headey) and Themistocles of Athens (Sullivan Stapleton) coming together to unite against the Persian Army. In real life, Athens and Sparta were indeed at the forefront of the alliance between the thirty Greek city-states. As the alliance took hold, Themistocles became the most powerful man in Athens.

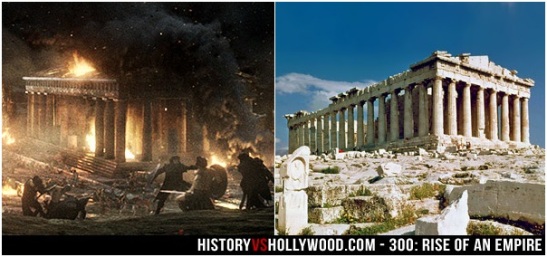

How were the Persians able to take Athens?

Themistocles had convinced Athens to put every able-bodied man, including the Athenian warriors, on warships to stop the Persians in the Straits of Artemisium, leaving the city of Athens unprotected. Plutarch writes of the evacuation of Athens in his work Themistocles. “When the whole city of Athens were going on board, it afforded a spectacle worthy alike of pity and admiration, to see them thus send away their fathers and children before them, and, unmoved with their cries and tears, passed over into the island.”

While it appears that the Parthenon (right) is burning in the movie (left), it is actually the Old Parthenon that was destroyed by the Persian forces during the invasion. The iconic Parthenon that we are familiar with was actually built several decades later to replace the Old Parthenon.

Did Themistocles win the Battle of Salamis by luring Xerxes into a trap?

Yes. Themistocles had sent a messenger to Xerxes, telling the Persian King that the Greeks intended to flee by ships that were harbored in the isthmus of Corinth. Unlike in the movie, that messenger was not Ephialtes of Trachis, the disfigured hunchback who had betrayed the Spartans at Thermopylae. The real Ephialtes, who was not a disfigured hunchback, escaped to Thessaly and the Greeks offered a reward for his death.

Thinking that the Greek forces were scattered, weak, and intending to flee, Xerxes believed the messenger and sent in his navy for an easy victory. To his surprise, his ships encountered the full force of the Greek navy ready to engage in battle.

Did Themistocles and Artemisia share a moment of violent, unbridled passion?

Artemisia (Eva Green) and Themistocles (Sullivan Stapleton) share a fictional moment of passion in 300: Rise of an Empire.

No. In what has become the most talked about scene in the movie, Artemisia invites Themistocles on board her warship in an attempt to lure him into abandoning Greece and joining her side. Before he convinces her that he will never abandon Athens, the two engage in a sexual tussle deep below deck that is the closed doors equivalent of any of the movie’s turbulent and ferocious battle sequences. In real life, not surprisingly, there is no record of a sexual encounter ever taking place between Themistocles and Artemisia. Despite this, the scene will very likely become what 300: Rise of an Empire is remembered for.

Was Themistocles married?

Yes. In the movie, Themistocles tells Artemisia that his only family is the Greek fleet, which he has spent his entire life readying to battle her. According to the writings of Plutarch, the real Themistocles did have a wife, Archippe, with whom he had three sons: Archeptolis, Polyeuctus, and Cleophantes. He also had two older sons, Neocles and Diocles. In addition to his sons, Themistocles had five daughters that are mentioned by Plutarch, at least one of whom he had later during a second marriage.

Did Xerxes watch the Battle of Salamis as he sat in his throne perched atop a cliff?

Yes. Xerxes watched the battle unfold high atop a nearby cliff on Mount Egaleo. Not shown in the movie, he witnessed Artemisia ramming another ship that had unknowingly crossed her path as she tried to get away from a pursuing Athenian trireme. Xerxes assumed it was an Athenian vessel that she had smashed through and was so impressed with Artemisia’s ferocity in battle that he is reported to have said, “My men fight like women, and my women like men!” In reality and unbeknownst to Xerxes, Artemisia had bore straight through an ally ship. In doing so, Artemisia’s pursuer gave up chase, believing that she was an ally of the Greeks. Fortunately for Artemisia, the ally ship sunk and its entire crew drowned, leaving no one behind to tell Xerxes the truth. -The Histories

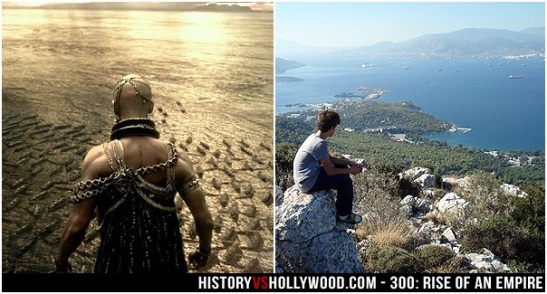

From high atop a cliff, Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro) overlooks his fleet in the Straits of Salamis in the movie (left). A look from the real Mount Egaleo that overlooks the Straits of Salamis where the battle took place (right).

Did Artemisia agree with Xerxes with regard to the Battle of Salamis?

No. However, unlike in the film where Artemisia (Eva Green) demands that Xerxes order the Persian fleet to Salamis to finish off the Greeks, the real Artemisia had actually advised the Persian King Xerxes against the battle, arguing that it is not wise to engage the Greeks at sea. By this point, Xerxes had already burned the great city of Athens to the ground. Victory was within his grasp and his advisers/officers, except for Artemisia, told him that he must launch a naval assault to finish off the Greeks. Artemisia saw things differently.

“Spare your ships,” Artemisia advised, “and do not risk a battle; for these people are as much superior to your people in seamanship, as men to women. What so great need is there for you to incur hazard at sea? Are you not master of Athens, for which you did undertake your expedition? Is not Hellas subject to you? Not a soul now resists your advance…” -The Histories

In the end, though Xerxes respected her advice, he still decided to launch a full-scale naval assault in September, 480 BC. Unfortunately for the Persians, it was the wrong decision and the Battle of Salamis proved to be the turning point in the war. Like in the 300: Rise of an Empire movie, the Persians were outmaneuvered and outfought by a Greek navy that was better prepared to wage war in the narrow straits between the mainland and the island of Salamis (known as the Straits of Salamis).

Artemisia (Eva Green) readies her bow during the Battle of Salamis in the 300: Rise of an Empire movie.

Did Artemisia die at the Battle of Salamis?

No. The 300: Rise of an Empire true story reveals that unlike what is shown in the movie, the real Artemisia did not die at the hands of Themistocles in the Battle of Salamis. She survived the battle and did not meet her fate while engaging in combat.

While Artemisia I of Caria did not perish in battle, it is unclear how she actually died. One legend reported by Photios, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 858 to 867 and from 877 to 886, has Artemisia falling in love with a man named Dardanus. According to Photios, when Dardanus rejected her, Artemisia threw herself over the rocks of Leucas and was swallowed by the Aegean Sea. However, some historians argue that this action goes against her nature as a strong-willed conqueror.

What happened to Artemisia after the Battle of Salamis?

After being on the losing side of the battle that she had advised the Persian King against, Xerxes once again sought her advice. This time he acted on it, and he returned home, abandoning his campaign.

Artemisia was entrusted with the care of Xerxes’s children (the illegitimate sons he had taken on the campaign with him). She accompanied them to the town of Ephesus on the Ionian coast. Despite the Greeks continuing to engage in war for several more years, Artemisia and her people gained favor with the Persian Empire and prospered from the relationship.

Where can I read Frank Miller’s graphic novel Xerxes, on which 300: Rise of an Empire is based?

As of the release of the 300: Rise of an Empire movie in March of 2014, Frank Miller had not yet completed his sequel to his 1998 comic series 300. In early 2011, Dark Horse Comics CEO Mike Richardson told ICv2 that Miller had finished two issues but had several Hollywood commitments that were keeping him from finishing the rest. These Hollywood obligations included acting as co-director for Sin City 2, due out in August 2014. The ICv2 article states that Frank Miller has every intention of finishing the Xerxes comic series.

The God King Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro) in the movie (left) and Xerxes from Frank Miller’s unpublished (as of the film’s release) graphic novel.

Why didn’t director Zack Snyder, who directed the first film, also directRise of an Empire?

In 2008, Variety reported that Zack Snyder, who directed 2007’s 300 starring Gerard Butler, was interested in directing an adaptation of Frank Miller’s follow-up graphic novel Xerxes (the original 300 movie was based on Miller’s 1998 graphic novel 300). However, Zack Snyder instead chose to direct the Superman reboot Man of Steel, released in 2013. As a result, Noam Murro was brought in to direct 300: Rise of an Empire with Snyder acting as a producer and co-writer (Deadline Hollywood).

5. Who was the real Artemisia? How accurate is Frank Miller’s 300 Rise of an Empire?

Themistocles: Better we show them, we chose to die on our feet, rather than live on our knees!

Anyone familiar with Frank Miller’s 2006 hit 300 should not be surprised to find its sequel, 300 Rise of an Empire, full of over-the-top images, exaggerated creatures, and completely unrealistic action sequences. But, despite 300‘s comic book stylization, the film stayed true to its ancient sources in many ways. Herodotus, Greece’s first great historian, fills his account of the Persian Wars with fantastic images, too. There are no lobster-handed people in Herodotus, and his Xerxes is not 9 feet tall, but there is a hunchbacked Ephialtes whose deformities contribute to his disloyalty, Leonidas’s Spartan guards are portrayed as nearly super-human, and, to Frank Miller’s credit, much of the action of the original movie follows the Herodotean account.

But, how about the new film? Does it show fidelity to the ancient history, too, or does it represent more of a departure? And what about Artemisia, in particular? Was there really a great and evil woman pulling the strings during the second Persian invasion?

There are dozens, if not hundreds, of inaccuracies in 300 Rise of an Empire–far more, I would argue, than in the original 300 film–but Artemisia is, indeed a real character in Herodotus’s Histories. She is an accomplished naval commander, according to Herodotus, as well as a respected adviser to Xerxes. And, she is singled out in Herodotus’s account for both of these things. There are no other female navalcommanders in Herodotus’s account of Xerxes’s Persia. He has no other military advisors who are women. So, Artemisia really was kind of a big deal.

On the other hand, there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that Artemisia had anything to do with Xerxes development (supernatural or not) as an emperor or that she had any relationship whatsoever with Darius. Neither is there any suggestion that she and Themistocles . . . um . . . “met.” In fact, the Herodotean account makes both of these elements of 300 Rise of an Empire entirely implausible.

The real Artemisia was not a villain (except perhaps from the perspective of Damasithymos, king of of the Kalyndians; but, we’ll need a little more context before we can make sense of that part of the story). Xerxes think she’s great, although he worries a bit that she might be a freak of nature. And, Herodotus, who was Greek, goes out of his way to paint her in a positive light.

Here’s what we know from Herodotus about Artemisia, and here are the passages from the Histories that tell us her story.

Artemisia’s first appearance in Herodotus’s Histories comes in Book 7, chapter 99 (7.99). After giving a list of the names of the Greek and Persian fleets, Herodotus tells us that he will tell us about only one “subordinatecommanders,” Artemisia.

Although I am not mentioning the other subordinate commandersbecause I am not compelled to do so, I shall mention Artemisia. I find it absolutely amazing that she, a woman, should join the expedition against Hellas. After her husband died, she held the tyranny, and then, though her son was a young man of military age and she was not forced to so so at all, she went to war, roused by her own determination and courage. Now the name of this woman was Artemisia; she was the daughter of Lygdamos by race part Halicarnassian on her father’s side, and part Cretan on her mother’s side. She led the men of Halicarnassus, Kos, Nisyros, and Klymna, and provided five ships for the expedition. Of the entire navy, the ships she furnished were the most highly esteemed after those of the Sidonians, and of all the counsel offered to the king by the allies, hers was the best. I can prove that all the cities under her leadership which I have just mentioned were Dorian, since Halicarnassians came from Troizen and all the rest came from Epidauros.

(The Landmark Herodotus, 7.99,trans. Andrea Purvis)

There’s a lot in this passage to unpack, but we’ll just pick out the big things.

- Artemisia was not kidnapped and abused as a child. She was the daughter of royalty, married a king, and had children.

- She was in charge not only of the fleet of her polis (city-state), but of several others, as well. She didn’t have to be. Her son was old enough to step up. But, she was motivated by “her own determination and courage.”

- She was, as the movie depicted, Greek–Dorian, specifically, rather than Ionian. This meant that ethnically, she was related to the Spartans. This wasn’t unusual, though, and it didn’t make her a traitor. There was no unified Greece in the 5th century BCE, and lots of ethnically Greek cities in Asia Minor (and even in what is now mainland Greece) had been “medized,” that is, gathered up into the Persian empire, both politically and culturally.

- Xerxes respected her for good ships, good military leadership, and good counsel. (She was a bad ass.)

The next time Artemisia shows up in the Histories, the Persians have burned Athens are trying to decide whether or not to engage the Greek fleet at Salamis, so we get to see her in action as Xerxes’s advisor.

So Mardonios made his way around and questioned them, beginning with the Sidonian. They all expressed the same opinion, urging him to initiate a battle at sea, except for Artemisia, who said:

“Speak to the King for me, Mardonios, and tell him what I say, since I have not proven to be the worst fighter in his naval battles of Euboea, nor have I performed the least significant of feats. Tell him, “My lord it is right and just that I express my opinion, and what I think is best regarding your interests. ‘Here is what I think you should do: spare your fleet; do not wage a battle at sea. For their men surpass yours in strength at sea to the same degree that men surpass women. And why ss it necessary for you to risk another sea battle. Do you not already hold Athens, the very reason for which you set out on this campaign? And do you not have the rest of Hellas, too? No one is standing in your way; those who have stood against you have ended up as they deserved.

“‘Let me tell you what I think your foes will end up doing. If you do land, or even if you advance to the Peloponnese, then, my lord, you will easily achieve what you intended by coming here. The Hellenes are incapable of holding out against you for very long; you willscatter them, and each one will flee to his own city. For I hear that thy have no food with them on this island, and if you lead your army to the Peloponnese, it is unlikely that those who came from there will remain where they are now and concern themselves with fighting at sea for the Athenians.

“‘But if you rush into a sea battle immediately, I fear that your fleet will be badly mauled, which would cause the ruin of your land arby as well. And there is one more thing that you should think about, sire, and keep in mind: bad slaves tend to belong to old people, while good slaves belong to bad people. And you, the best of all men, have the worst slaves, who are said to be included among your allies, namely the Egyptins, Cyprians, clinicians, and Pamphylians: they are absolutely worthless.’”

As Artemisia was speaking to Mardonios, all those who were well-disposed toward her thought her words most unfortunate, since they believe she would suffer some punishment from the King for telling him not to wage a battle at sea. On the other hand, those who were envious and jealous of her, because she was honored as one of the most prominent of the allies, were delighted by her response to the question, thinking that she would perish for it. When these opinions were reported to Xerxes, however, he was quite pleased with Artemisia’s answer. Even prior to this, he had considered her worthy of his serious attention, but now he held her in even higher regard. Nevertheless, his orders were to obey the majority; he strongly suspected that off Euboea they had behaved like cowards because he was not present, but now he was fully prepared to watch them fight at sea. (8.68-69)